Single copy purchase

Per Macmillan’s new policies with regard to library eBook purchases:

We will make one copy of your ebook available to each library system in perpetuity upon publication. On that single copy we will cut the price in half to $30 (currently first copies are $60 and need renewal after two years or 52 lends). This change reflects the library request for lower prices and perpetual access. Additional copies of that title will not be available for library purchase until 8 weeks after publication.

Theoretically, being able to buy one copy of a title and hold it in perpetuity is a good idea. In practice, it will deceptively communicate to borrowers for eight weeks that library wait times are incredibly long. CEO John Sargent is open about creating friction for borrowers. Opening Libby and seeing years-long wait times will do that.

Let’s look at how this works.

Note: for those who are unfamiliar with eBook borrowing, our eBook catalog apps and websites let readers know how long they will have to wait for a title. Libraries control the wait time by purchasing a new copy every time there are a certain number of requests for it. That number varies by library.

At my eBook consortium, we buy a new copy for every seven requests, and we allow a maximum individual checkout period of three weeks, so the longest that anyone will have to wait for a book is 21 weeks.

We purchase eBooks weekly based on requests to ensure that when readers view on their apps how long they will have to wait, the time period is fairly accurate.

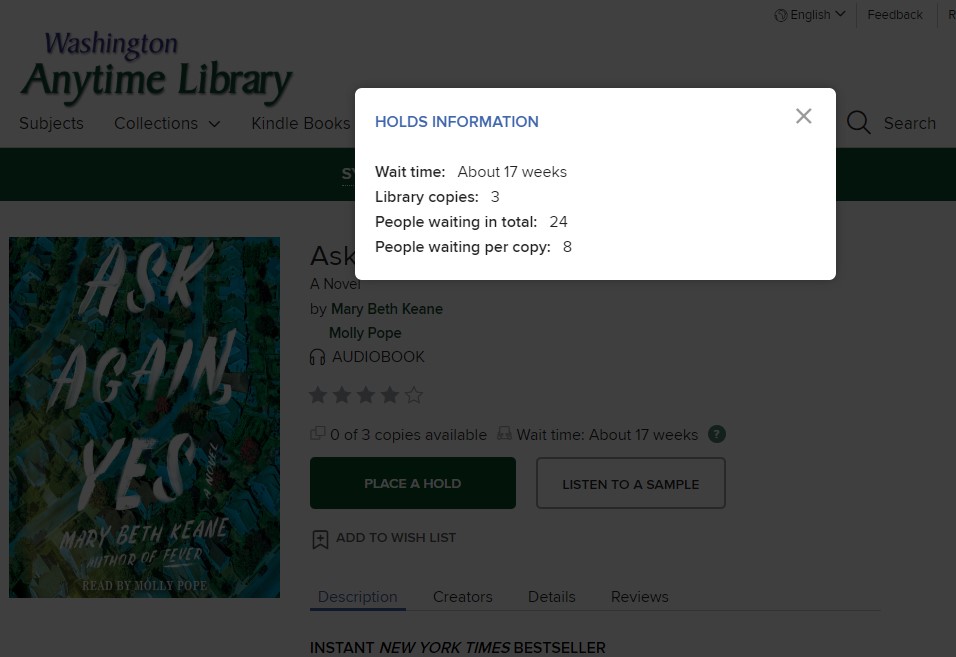

For example, the audiobook Ask Again, Yes by Mary Beth Keane shows the following information as I write this:

- Wait time: About 17 weeks

- Library copies: 3

- People waiting in total: 24

- People waiting per copy: 8

Because eight people are waiting per copy for this title, and because we have enabled a setting to alert us when more than seven people are waiting per copy, OverDrive’s software will automatically add this Ask Again, Yes to a candidate purchase list and our selectors will review the following week. They will buy another copy, and the information about the waiting time will adjust accordingly to:

- Wait time: About 13 weeks

- Library copies: 4

- People waiting in total: 24

- People waiting per copy: 6

Now, let’s look at how this will work when we are allowed only to buy one copy of a book for the eight weeks when it is most likely to be requested. This particular title is from Simon & Schuster, not Macmillan, but if a similar Macmillan title is embargoed, and garners 24 requests, the dialog will say for up to eight weeks:

- Wait time: About 49 weeks

- Library copies: 1

- People waiting in total: 24

- People waiting per copy: 24

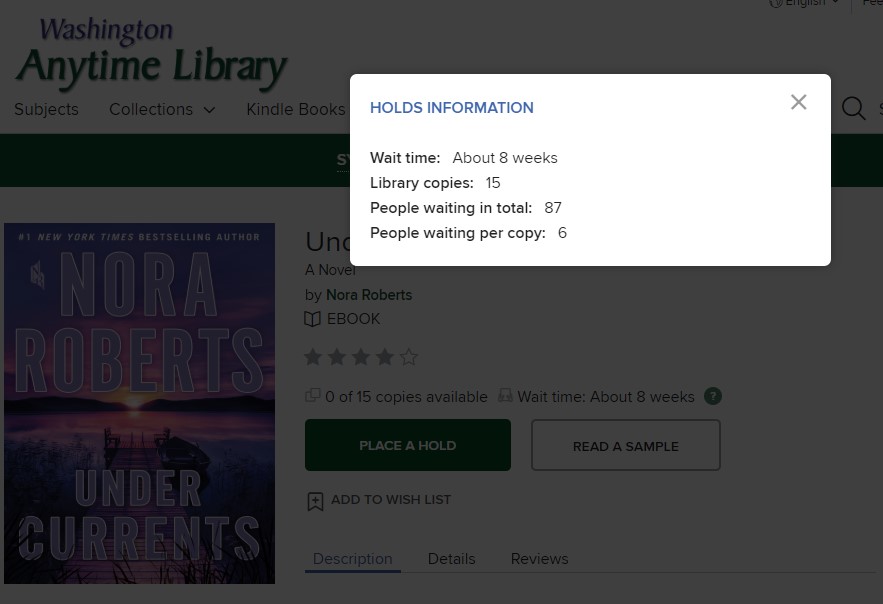

If we consider best-sellers, the situation is even worse. The wait list information for Nora Roberts Under Currents currently says:

- Wait time: About 8 weeks

- Library copies: 15

- People waiting in total: 87

- People waiting per copy: 6

If Nora Roberts comes out with a similar title next year, it will be embargoed. And if libraries buy a single copy on the release date, it will say, for eight weeks:

- Wait time: About 3 years and 4 months

- Library copies: 1

- People waiting in total: 87

- People waiting per copy: 87

Of course, in week nine, we will buy 14 copies to restore the correct wait time, but for eight weeks, the app will show deceptive information.

Consider also that this will appear random to the patrons. Some best sellers will have short wait lists. Some will have long wait lists. There is no good way for the patron to identify the culprit: Macmillan. So they will kill the messenger: the library.

It is worthwhile to think through that conversation.

Exasperated Patron: What the heck? My Libby app says that I have to wait more than three years for Nora Roberts.

Library staff: Yes, we are sorry about that confusion. The wait time will not really be that long.

Patron: Well, how long will it be and why is the app wrong?

Library staff: Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing how long your wait will be.

Patron: What? Why?

Library staff: It’s a publisher restriction. We only know real wait times after the book has been out for 9 weeks. Let me give you a copy of the library eBook lending terms for this particular publisher. We know that it’s frustrating and we encourage you to pass along your feedback to Macmillan.

Patron: I don’t want to pass along feedback. I just want to know when I’m going to get my book!

If we avoid buying the $30 copy, we guarantee that the information patrons see in Libby or OverDrive is accurate and truthfully reflects our buying polices and real wait times. We avoid the cost of conversations like the above.

It’s possible that the eLending platforms like OverDrive will drop the projects they’re working on now and adapt the formula they use for calculating wait times to accommodate Macmillan’s policies, but it is unlikely they will release a fix by November 1. And, I am not sure if they can implement a fix at all.

Being able to predict wait times accurately requires that libraries always buy according to a holds ratio. My library consortium does, but I know of others who use hold ratio reports but pick and choose what copies to add to the collection depending on budget constraints. In other words, for those libraries, the wait times that patrons see will never be reliable. Technically, only the wait times for Macmillan titles will be less accurate — all other publishers will continue to show accurate wait times — but borrowers will not know the difference.

I doubt that Macmillan understands library user experiences well enough to have intended this debacle, but their goal is to increase their sales by creating friction in borrowing. And now, one of the features borrowers rely upon will be less accurate at best and deceptive at worst. We do not want patrons to be hoodwinked into buying books because wait times look worse than they are.

Patrons trust libraries to tell them the truth. Let’s ensure that our purchases enable us to do that.